Ah, intussusception, the Mississippi (at least in terms of spelling) of medicine. For my latest series I thought I’d look into this common diagnosis in the Peds ED.

Is it really that common?

Well, it is the #1 cause of intestinal obstruction in children 6 months to 36 months. So, its got that going for it, which is nice. 60% are <1 year and 90% are <2 years. It is rare before age 3 months and after age 3 years. Boys to girls ratio is 3:2 and most cases occur in regular, healthy kids.

What exactly is it?

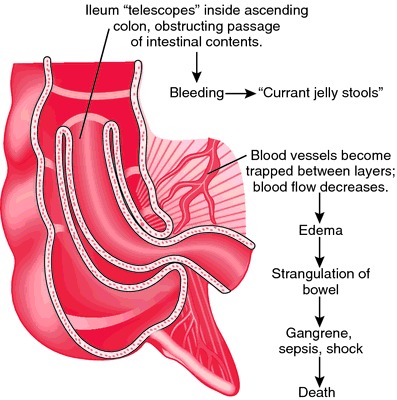

Think about intussusception like a collapsible telescope. One piece of bowel – the proximal intussusceptum, usually the ileum, slides into another piece – the distal intussuscipiens – usually the colon and gets momentarily stuck. The intussusceptum drags its blood supply and associated mesentery with it. This hurts because the resulting venous and lymphatic congestion leads to intestinal edema. As time goes on the swelling increases, and you can see ischemia, perforation and peritonitis – all of which are generally bad. The pain is initially crampy/colicky and intermittent. Children are often inconsolable, and will draw their knees up to their abdomen. They occur 15-20 minutes apart – though frequency and severity increase as intestinal edema increases. Some children vomit, and in cases of a “stuck” intussusception it can be bilious. Initially children are pain-free and appear well in between episodes. Over time, as acidosis develops they become more lethargic. Very sick children with intussusception an look like they have sepsis!

On exam, you may see the episodes of pain, and you could feel a sausage-shaped abdominal mass on the right side of the abdomen. Eventually, 70% of cases have occult and/or gross blood. The mix of blood/mucous is known as currant jelly stools, and generally this means that mucosal necrosis has occurred to some extent.

From virtualpediatrichospital.org

On the boards you’ll note that the following “classic triad” is frequently referenced:

- Pain

- Palpable sausage shaped abdominal mass

- Currant-jelly stools

The classic triad only seen in 15% of patients!

Here is a helpful diagram of what happens.

Why does it happen?

Most cases cause providers to throw up their hands and say “I dunno?” To put it another way, fully 75% of case are idiopathic. Other factors thought to be contributory include:

- Viral illnesses: peaks may coincide with viral illnesses which may lead to swelling of the Peyer’s patches of the intestinal lumen, thus creating a potential lead point. Up to 30% of patients have some sort of viral illness (URI, OM, flu-like illness) relatively recently before having intussuscpetion. Adenovirus may also increase the risk

- Early versions of the Roatvirus vaccine (Rotashield™) which was removed from the market

- Bacterial intestinal infections – Nylund et al saw an increased association with Salmonella, E. coli, Shigella, or Campylobacter

- Underlying conditions — 25% of cases are felt to be related to something else that causes a lead point to develop and are responsible for a greater proportion of the cases in children <3 months and > 5 years. Examples include Meckel diverticulum (the most common of these), Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyps and hamartomas, Chron’s disease, Cystic Fibrosis, parasites, and Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (maybe because of the bacterial infection).

- Postoperative small bowel-small bowel – usually reduces on its own – and can be misinterpreted as ileus

Tune in next time as we discuss diagnosis.

[…] Welcome to part 2 of the intussusception series – check out part 1 here. […]

[…] you’ve checked out part 1 and part 2 – Let’s now shift the focus to the […]

[…] in PEM Cincinnati, Brad Sobolewski tackled intussusception in a 3-installment post – it’s always there at the back of our minds for every abdo pain we see in PED and this is […]