It’s not the heart way more often than it is the heart when it comes to pediatric syncope in the Emergency Department. The purpose of this post is to highlight factors in the history and physical examination that should make you think that it could actually be the heart – and get pediatric cardiology involved.

This post specifically focuses on kids that are well appearing, and can help you make the decision on whether or not to refer a child to pediatric Cardiology versus follow up with their Primary Care Doctor.

When syncope occurs you should be worried if…

It happened in a child who is under 8 years old

This one takes a good history. Think about a toddler who has a report of loss of consciousness. If you take a really good history you’ll probably establish that it was a breath holding spell, which is technically a syncopal event, and usually due to vagal mechanisms. I did a podcast on breath holding spells if you are interested.

It was during exercise

This is one that we should take a little time to explore on history. Obviously it is worrisome if the patient syncopizes while running in a cross country meet. During exercise doesn’t mean that you have to be actively running, lifting weights etc,. It just means that one was exerting themselves and then they fainted. Obviously the big diagnosis to worry about here is hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. But anything that limits ventricular outflow (aortic stenosis) is on the table as well.

It was preceded by chest pain

Though these symptoms sometimes occur with vasovagal syncope, a carful history can help you get at this symptom. Remember, most kids will describe lightheadedness, visual changes etc,. before they fainted. Chest pain is actually relatively rare.

It was accompanied by significant physical injury from a sudden fall

Patients with syncope often go down quickly, but many are witnessed, and helped to the ground. Or gently catch themselves – and slump to the ground. Patients who sustain major trauma (a clinically important brain injury) went down hard and the event may have been sudden, and potentially worrisome.

There was a near drowning

This one is relatively rare (fortunately) but if someone faints and almost drowns then worry that something seriously happened. First, you should wake up if you go under water because of protective responses. And second, if you don’t anoxic injury can set in relatively quickly.

There was seizure activity with a postictal state

Remember, up to 40% of people who faint will convulse. But most recover very quickly. A patient who took longer than 20-30 minutes to recover should cause you to think a little more about what lead to the episode of loss of consciousness and why the patient didn’t recover as quickly. Please check out my post on convulsive syncope for helpful information, including a fantastic video that demonstrates the myriad of different abnormal movements that occur following syncope.

There are focal neurologic findings after the syncopal event

This one can go hand in hand with the previous one. You must do a good neurologic exam. Make sure to differentiate from pain caused by an injured wrist for instance, from somebody with asymmetric weakness. Patients who have syncope should not have an abnormal neurologic examination.

First degree family history red flags

This one does not include Uncle Steve or Great Aunt Barbara. I’m sure that those people are wonderful humans, but per Cardiology, only first degree relatives count when it comes to worrisome history in syncope.

Cardiomyopathy

Many non-medical folks will not know what this is. Cardiomyopathy is broadly defined, and occurs in a number of settings; post viral, in pregnancy, after an acute cardiac event and more. Furthermore, there are different subtypes, dilated, restrictive. I therefore recommend the following lay definition that will at least get across the gist of what Cardiomyopathy is;

“A disease of the heart muscle that makes it harder for that heart to pump blood to the rest of your body.”

MayoClinic.org

Sudden death in someone less than 50 years old

This one can be hard to nail down in the history as well. It can also dredge up difficult memories. Perhaps someone died of cardiac arrest following a drug overdose for instance. I would recommend asking specifically if a first degree relative died before they were 50, and the case was known to be due to the heart. For instance, a heart attack.

A known arrhythmia like long QT syndrome or Brugada syndrome

This is another one that people won’t know about unless they are in medicine, or have a family member with it. Again, describing the problem in lay terms, about an abnormal heart rhythm that is inherited or medication induced that can lead to syncope or even sudden death.

A family member under 50 has a pacemaker or defibrillator

It is relatively uncommon to get a pacemaker or implantable defibrillator when you are under 50. Even if they don’t know precisely why, it should at least make you curious about what kind of heart condition a family member has if they have a heart fixing computer embedded in their chest wall connected to their heart. Per Healey et al, the average age for pacer implantation is 75 years of age, with sick sinus syndrome and AV block being among the most common reasons. Only 6% of patients with a pacemaker are under 50.

Specific EKG findings

QTc interval >470 msec

Remember, this is one that we calculate manually, using an accepted tool or equation. The one that many of us were taught is:

QTc = QT interval ÷ √RR interval [in sec]

Long QT syndrome can lead to syncope and sudden cardiac death. So if the calculated measurement (not the one the EKG spit out) is longer than 470 msec refer the patient to Cardiology.

Pre-excitation

Patients with pre-excitation have an accessory pathway that bypasses the AV node. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is the existence of pre-excitation on EKG and an episode of tachycardia. Per an excellent post on Life in the Fast Lane the main EKG features of pre-excitation are:

- PR interval <120ms

- “Delta wave” slurring slow rise of initial portion of the QRS

- QRS prolongation >110ms

- ST Segment and T wave discordant changes – i.e. in the opposite direction to the major component of the QRS complex

- Pseudo-infarction pattern can be seen in up to 70% of patients – due to negatively deflected delta waves in the inferior / anterior leads (“pseudo-Q waves”), or as a prominent R wave in V1-3 (mimicking posterior infarction)

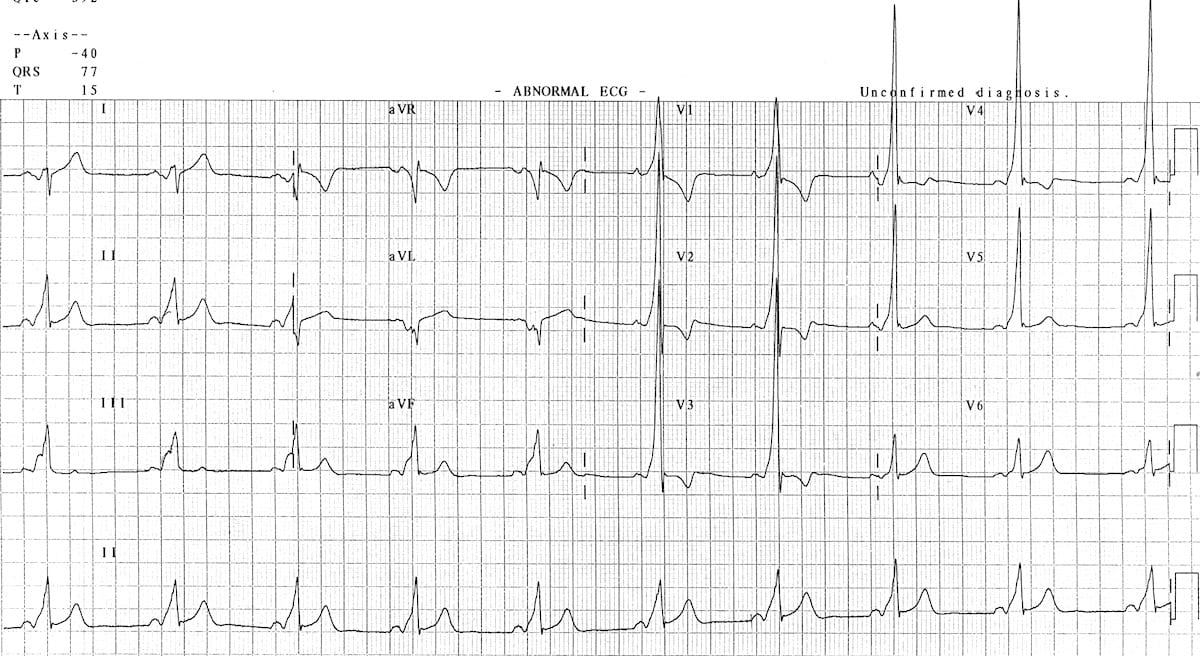

Brugada pattern

Brugada is a pseudo-right bundle branch block (RBBB) and persistent ST segment elevation in leads V1 to V3. You’ll see ST segment elevation >2mm in >1 of V1-V3 followed by a negative T wave. It is a genetic sodium channel mutation. A sample of the waveform is seen below. The mean age of sudden death is 41. It has a much higher prevalence in Southeast Asia.

Abnormal voltage and intervals

You need to have access to age and gender-based norms and make sure you calculate all of the peaks an intervals. This is part of doing the work to make sure a patient is safe or if the need to be referred to Cardiology. There are some simple “hacks” you can remember though. Abnormal findings for ventricular hypertrophy, adapted from Evans et al, and borrowed from Ped EM Morsels include:

- Abnormal Left Ventricular Large Voltage (“LVH”)

- Use only V6 (the left most precordial lead)

- If R wave of V6 intersects with baseline of V5, then that is abnormal.

- Abnormal Right Ventricular Large Voltage (“RVH”)

- Use only V1 (the right most precordial lead)

- Upright T wave in V1?

- During 1st week of life, T wave can be upright in V1.

- After 1st week of life, upright T wave in V1 is abnormal in children until adolescence.

- With RSR’ is present, if R’ is taller than R wave, then this is abnormal.

- A pure R wave in V1 in a child > 6 months of age is abnormal.

You should also refer for First degree AV block with a PR interval >250 msec.

Pathological ST segment changes

The main point that I want to make here is that many healthy teens will have a subtle upsloping of the ST segment immediately after the QRS complex. This is sometimes called “J-point elevation” or early re-polarization, and is seen in healthy young hearts. ST elevation in grown ups makes one think of myocardial infarct. Benign early depolarization can be seen in 1 of 10 patients with chest pain presenting to the ED, so how do you tell the difference? First, get good at looking at EKGs. Here are some examples of early depolarization, again courtesy of Life in the Fast Lane:

It is also common to see “notching” of the J-point in benign early depolarization. This gives the ST-segment a “fish hook” appearance as seen in the embedded image. This notching is generally best seen in lead V4.

Note that early depolarization can be more prominent with slower heart rates. There is also a validated calculator that will help you differentiate early depolarization from STEMI. It is most useful in patients with a suspicious history for MI, but a non-diagnostic EKG. It involves calculating/measuring the following 4 things and using the following formula:

Subtle Anterior STEMI 4-Variable Calculation = 0.052 x (Bazett-corrected QT interval, ms) - 0.151 x (QRS amplitude in lead V2, mm) - 0.268 x (R wave amplitude in lead V4, mm) + 1.062 x (ST segment elevation 60 ms after the J point in lead V3, mm)

Or you could just use the calculator found at MDCalc. Your choice…

Examination findings

Some specific examples include:

- A systolic ejection murmur and/or an ejection click which are heard in aortic stenosis

- A difference in pulse quality in upper and lower extremities (upper > lower), and a difference in upper and lower extremity systolic blood pressures arm 20 mmHg or more greater than leg, can be seen in coarctation of the aorta

- A murmur that is heard in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is one that decreases in intensity with increased venous return to the heart (during a Valsalva or squatting)

- Rales on lung exam (not really the heart exam)

- A friction rub or gallop

- A LOUD S2

- Hepatosplenomegaly (unless the patient concurrently has mono and faints) can be indicative of heart failure

- Rales on lung exam are also a sign of heart failure

References

Evans WN, Acherman RJ, Mayman GA, Rollins RC, Kip KT. Simplified pediatric electrocardiogram interpretation. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010 Apr;49(4):363-72. PMID: 20118092.

Fox S. Pediatric ECG. Pediatric EM Morsels. https://pedemmorsels.com/pediatric-ecg/. September 8, 2017. Accessed February 7, 2020.

Friedman KG, Alexander ME. Chest pain and syncope in children: a practical approach to the diagnosis of cardiac disease. J Pediatr. 2013 Sep;163(3):896-901.e3. Epub 2013 Jun 12.

Healey JS, Toff WD, Lamas GA, Andersen HR, Thorpe KE, Ellenbogen KA, Lee KL, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with atrial based pacing compared with ventricular pacing: Meta-analysis of randomized trials, using individual patient data. Circulation 2006; 114:11–17.

Hurst D, Hirsh DA, Oster ME, Ehrlich A, Campbell R, Mahle WT, Mallory M, Phelps H. Syncope in the Pediatric Emergency Department – Can We Predict Cardiac Disease Based on History Alone? J Emerg Med. 2015 Jul;49(1):1-7. Epub 2015 Mar 20.

Gillette PC, Garson A Jr. Sudden cardiac death in the pediatric population. Circulation. 1992;85(1 Suppl):I64.